Hunter lived and worked most of her life on the Melrose cotton plantation near Natchitoches, Louisiana. She did not start painting until the 1940s when she was already a grandmother. Her first painting, executed on a window shade using paints left behind by a plantation visitor, depicts a baptism in Cane River.

Hunter painted at night, after working all day in the plantation house. She used whatever surfaces she could find, drawing and painting on canvas, wood, gourds, paper, snuff boxes, wine bottles, iron pots, cutting boards, and plastic milk jugs.

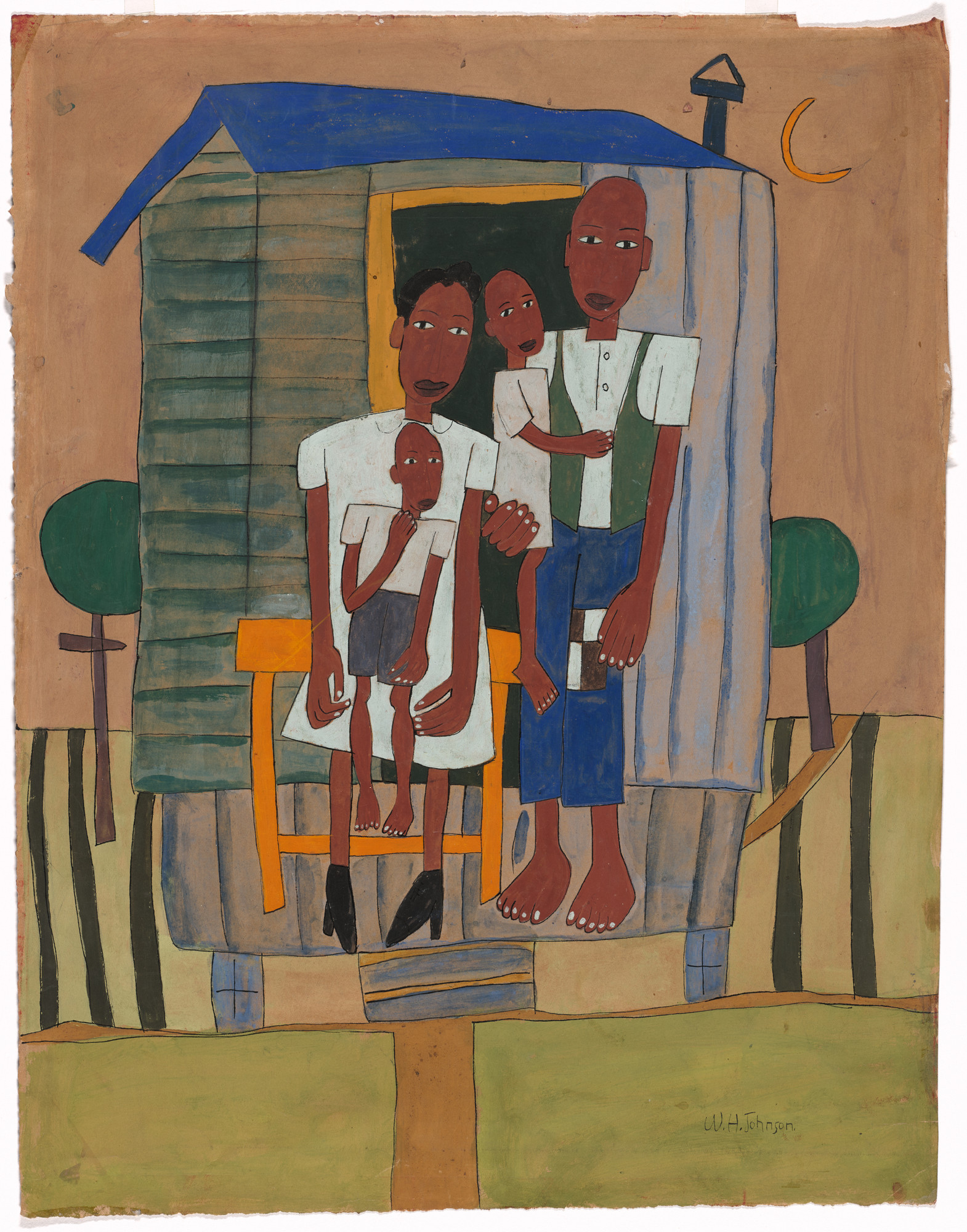

Working from memory, Hunter recorded everyday life in and around the plantation, from work in the cotton fields to baptisms and funerals. She rendered her figures, usually Black, in expressionless profile and disregarded formal perspective and scale.

Though she first exhibited in 1949, Hunter did not garner public attention until the 1970s when both the Museum of American Folk Art in New York and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibited her paintings.

Even with such success, Hunter chose to stay in Louisiana, working at Melrose Plantation until 1970 when she moved to a small trailer a few miles away on an unmarked road.

SOURCE: CLICK HERE

Clementine Hunter was Louisiana's most celebrated and beloved folk artist. She is also Louisiana's most famous female artist. Hunter a self-taught African-American artist from the Cane River region of Louisiana, lived and worked on Melrose Plantation. Her work depicted plantation life in the early 20th century, documenting a bygone era. Her first paintings sold for as little as 25 cents. By the end of her life, her works were exhibited in museums around the world and sold by dealers and galleries for thousands of dollars. Hunter was the granddaughter of a former slave. Hunter received an hoary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Northwestern State University in 1986. Though she is considered a folk artist legend, she spent her entire life in poverty, even though she was selling her pieces of art in the 1970's for hundreds of dollars. She died in 1988 in Natchitoches, Louisiana.

Hunter is one of the most well-known self-taught artists, often referred to as the black Grandma Moses. Hunter painted from memory, and her works portray cotton and pecan picking, washing clothes, baptisms, and funerals. Many of her paintings feature similar subjects, but each painting is unique. Hunter's work features colorful displays of plantation life with powerful expressive force.

Hunter was the first African-Amerian artist to have a solo exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and prominent collectors include Oprah Winfrey and the late Joan Rivers, among many others . Her work can also be seen in the Smithsonian Institute, the Museum of American Folk Art, the Dallas Museum of Fine Art, and the New York Historical Association.

SOURCE: CLICK HERE

CLICK HERE FOR RESOURCES TO HELP YOU TEACH ABOUT BLACK ARTISTS